Rilwan – Disappearance of a Young Maldivian Storyteller

by Mushfique Mohamed

It has been 21 days since Ahmed Rilwan Abdulla, 28, a Maldivian journalist working for online news outlet Minivan News was last seen. Around 2am on 8th August, Rilwan’s neighbours in Hulhumalé reported seeing a man being forced into a car with his mouth covered. A knife was uncovered at the scene and police later took witness statements from those who reported the abduction. Efforts by the authorities into locating the reported abductee on 8th August were abysmal, creating more room for speculation into connection between the alleged abduction and the journalist who was reported missing by his family on 13th August. When Rilwan’s family made the missing person’s report, police took over 35 hours to conduct a search and seizure pursuant to it.

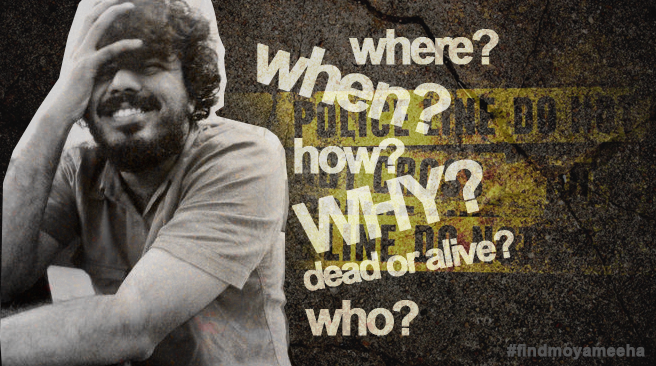

Rilwan, Rizwan or his pseudonym “Moya meeha*”, well-known and admired in the Maldivian blogosphere and twitterverse last contacted his employer around 1:45am through Viber on 8th August, his last tweet was made earlier at 1:02am. Chief Inspector  of Maldives Police Service (MPS) stated that the last signal received from Rilwan’s phone was at 2:30am that night, near Henveiru in Malé. MPS confirmed that he had not left the country and officially requested assistance from the public on 14th August. With a sense of fleeting time to find Rilwan safe, family, colleagues and friends conducted a coordinated search of Hulhumalé, an artificial island administratively run as a suburb of Malé. Maldives’ police were suspiciously slow off the mark; MPS conducted searches on the island only on 16th August, albeit for 3 consecutive days. Authorities failed to allocate a reward for him but Rilwan’s family increased their initial reward to 200,000 MVR (approximately 13,000 US$) for those with substantial information leading to finding him successfully.

of Maldives Police Service (MPS) stated that the last signal received from Rilwan’s phone was at 2:30am that night, near Henveiru in Malé. MPS confirmed that he had not left the country and officially requested assistance from the public on 14th August. With a sense of fleeting time to find Rilwan safe, family, colleagues and friends conducted a coordinated search of Hulhumalé, an artificial island administratively run as a suburb of Malé. Maldives’ police were suspiciously slow off the mark; MPS conducted searches on the island only on 16th August, albeit for 3 consecutive days. Authorities failed to allocate a reward for him but Rilwan’s family increased their initial reward to 200,000 MVR (approximately 13,000 US$) for those with substantial information leading to finding him successfully.

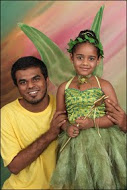

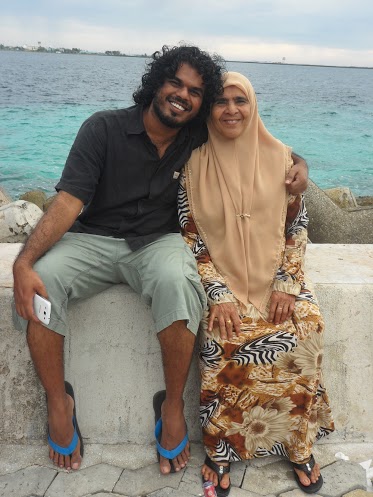

At Minivan News Rilwan covered a variety of stories, from environmental, juridical and human rights issues, to religious radicalism, re-introduction of the death penalty, corruption and immigration. Disturbingly, one of the last stories he covered was that of 15 Maldivian journalists who received death threats over coverage of gang-related violence. His family describe him as someone who is passionate about the Dhivehi language, history, folklore and poetry. Relatives in the video plea made for Rilwan say that it was very important for him to not harm others and to defend human rights. Tweets from friends also describe him as being “intelligent and well-versed with a variety of subjects”. After studying journalism in India, Rilwan worked for Jazeera News and the Human Rights Commission of Maldives (HRCM). He later joined local newspaper Miadhu before becoming a Minivan News journalist in December 2013.

On 21st August Maldives’ police conducted searches into certain houses in Malé, however, no information has been disclosed regarding these searches, or whether anyone has been arrested pursuant to Rilwan’s alleged abduction. CCTV footage from the ferry terminal in Malé clearly shows two men following Rilwan’s movements. It was his family and friends that expeditiously retrieved the CCTV footage and attempted to identify him on 15th August. On 27th August immigration confirmed that four passports were withheld in relation to Rilwan’s disappearance. The same day, Haveeru News reported that it had information that police seized a car a week ago regarding the reported abduction on 8th August. The authorities’ poor and delayed reaction to this incident has resulted in public outrage and fear within society. The media campaign created by his friends, colleagues and family presents to the viewer an unsettling possibility, “Where is Rilwan? Am I next?”.

On 21st August Maldives’ police conducted searches into certain houses in Malé, however, no information has been disclosed regarding these searches, or whether anyone has been arrested pursuant to Rilwan’s alleged abduction. CCTV footage from the ferry terminal in Malé clearly shows two men following Rilwan’s movements. It was his family and friends that expeditiously retrieved the CCTV footage and attempted to identify him on 15th August. On 27th August immigration confirmed that four passports were withheld in relation to Rilwan’s disappearance. The same day, Haveeru News reported that it had information that police seized a car a week ago regarding the reported abduction on 8th August. The authorities’ poor and delayed reaction to this incident has resulted in public outrage and fear within society. The media campaign created by his friends, colleagues and family presents to the viewer an unsettling possibility, “Where is Rilwan? Am I next?”.

Maldives’ private media outlets released a joint statement on 23rd August expressing grave concern over the disappearance of a fellow journalist. “Efforts have always been made by various parties to silence journalists. Many journalists have been assaulted. Murder attempts have been made as well. TVM and DhiTV were vandalised while VTV and Raajje TV were torched. Now, a journalist has disappeared without a trace,” read the statement. Furthermore, the statement suggests, “information [they] have gathered so far strongly suggests Rilwan was abducted.”

Unity among Maldives’ media to condemn attacks to press freedom is commendable and exceptional given ideological and editorial fissure within most local media outlets. The Yameen administration’s responses to ensure safety from threats made to politicians, journalists and secularists have been unsatisfactory as to support allegations of complacency or complicity. “It is the state’s responsibility to make relevant policies and laws to ensure this right for every Maldivian. However, sadly this worsening wound is festering without any treatment. As a result, extremism of all forms is becoming stronger, and the danger of gangs is growing” the statement continued.

Rilwan’s family and friends gathered at the People’s Majlis (parliament) on 25th August, while his mother submitted a letter, asking the Members of Parliament to hold MPS to account and expedite the investigation into her son’s mysterious disappearance. “I beseech you, as Speaker of the Majlis, prioritise this important case, and for the sake of all Maldivians, question Commissioner of Police to find out the truth. I plead with you; find out how my son is. Please take all necessary steps through the Majlis,” read the letter. The family asserted that past occurrences where Rilwan’s writings and views attracted death threats were reported to Maldives Police Service each time. With the letter, Rilwan’s mother outlined the gravity of her son’s situation to parliamentarians. She writes, “given the dire context of this incident; set in today’s society where there are unjustifiable assaults, reports of kidnapping or enforced disappearances and death threats, from unlisted numbers, made to young writers and journalists,” MPS has not provided adequate information on the progress of the case to the victim’s family.

Death threats, knife-crime and abductions are not uncommon in the tiny Arabian Sea-Indian Ocean archipelago that recently introduced multi-party democracy in 2008. The first democratically elected president Mohamed Nasheed, was first detained in solitary confinement by former leader Maumoon Abdul Gayoom for an article he wrote, published on ‘The Island’, a Sri Lankan newspaper in 1990. While crime rates in Maldives heavily increased, freedoms introduced during Nasheed’s government were met with staunch critics of democracy who deployed religious rhetoric and faux postcolonialism.

Death threats, knife-crime and abductions are not uncommon in the tiny Arabian Sea-Indian Ocean archipelago that recently introduced multi-party democracy in 2008. The first democratically elected president Mohamed Nasheed, was first detained in solitary confinement by former leader Maumoon Abdul Gayoom for an article he wrote, published on ‘The Island’, a Sri Lankan newspaper in 1990. While crime rates in Maldives heavily increased, freedoms introduced during Nasheed’s government were met with staunch critics of democracy who deployed religious rhetoric and faux postcolonialism.

Openly gay Maldivian blogger and human rights activist Hilath Rasheed was the victim of an attempted murder in June 2012. He led a silent protest promoting religious freedom and tolerance in the Maldives on Human Rights Day in 2011. The protest took place a month after the Nasheed administration was labeled anti-Islamic by an alliance consisting of Islamists and dictator-loyalists. Events such as, the monuments that were brought for the SAARC Summit considered “idolatrous” by Islamists; UN Human Rights Chief Navi Pillay’s comments regarding flogging made at the People’s Majlis; in November 2011, and reports that Israeli airline Al-El would operate from Malé International Airport earlier in May 2011 were used effectively to brand Nasheed “unIslamic.” Maldives’ police failed to investigate those who attacked the silent protestors, giving impunity to intolerance and radicalism. Momentum amassed from Islamist rhetoric resulted in the 23rd December politico-religious alliance in defence of Islam, which eventually saw the ouster of former President Nasheed in February 2012 in a bloodless coup.

Moderate PPM MP Afrasheem was brutally murdered in October 2012 after publicly apologising for comments he made which were deemed “unIslamic” by fundamentalists. Opposition aligned Raajje TV journalist Ibrahim Asward Waheed suffered a near fatal attack the same year after televising an empirical report on Gayoom era corruption. Since the disappearance, threats have increased, with Minivan 97 journalist Aishath Aniya, Raajje TV journalist Ahmed Fairooz, V News editor Adam Haleem, Maldivian Democratic Party (MDP) MPs Mariya Didi and Eva Abdulla, Jumhooree Party leader Gasim Ibrahim publicly claiming to have received death threats via text message. Earlier this year in June, Minivan News was the only local news outlet that covered a series of attacks on individuals perceived to be atheists, secularists or homosexuals by a group consisting of radical Islamists and prominent gang members in Malé.

The nexus between religious radicalisation of prisoners is clear and well documented. The BBC reported in May 2014 that there were around 100 Islamist terrorists in prisons in England and Wales. In Maldives where Islam is the state religion, authorities endorse fundamentalism perceiving it to be repentance or rehabilitation. By providing fundamentalist sermons and allowing only such reading material for inmates, the problem is worsened. Radicalisation denotes that these terrorist groups are willing to engage in violence to achieve political aims, distinguished from those who are fundamentalist without violent activism. As Islamism is a fundamentalist and politicized interpretation of Islam – observable in modern times – crimes committed in its name by radicals are both religious as it is political.

A report authored by Peter R. Neumann based on country reports on prison radicalisation and de-radicalisation from 15 countries; Algeria, Egypt, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, United Kingdom, United States, Israel, Singapore, Netherlands, Philippines, France, Indonesia, Afghanistan and Spain outlines instances where prisons can be a ‘hotbed’ for radicalism, but also cites methods by which inmates can be “de-radicalised or disengaged; collectively or individually” through prison policies and programmes. The report carried out between May 2009 and May 2010 by the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation and Political Violence (ICSR), claims that there are varied instances where prisoners affiliated with radical Islamist groups to propagate their politico-religious ideology and recruit fellow inmates. The 2013 US Department of State country report on terrorism states that there is concern in the Maldives for young inmates increasingly viewing transnational jihad as an attractive prospect. The prevalence of Takfiri ideas among Islamists, coupled with adolescent gang-related crime and political violence has created an environment that fails to safeguard freedom of press, freedom of speech and freedom of belief.

A 2012 report published by the Asia Foundation lead by Dr. Aishath Ali Naaz notes that religious education gang members have received in school “is insufficient to deter them from violence.” The report highlighted the exploitation of gangs in Malé by politicians and businessmen who use them as means to achieve political ends. The Yameen administration, which came to power on the premise of strong anti-secular rhetoric, continues a policy of reticence, denial and inaction, thereby fostering connections between Islamist radicalism, political polarization and increasing gang culture in Malé. Meanwhile his brother, former strongman Maumoon, continues to whip up ultranationalism, recently warning Maldivians of “irreligious” and “secular” ideas gaining prevalence in society. Statements have been made on 20th August regarding Rilwan’s disappearance by international bodies such as UN Human Rights Commissioner, and media associations such as Reporters Without Borders, CPJ, IFJ and South Asia Media Solidarity Network on 19th August, as well as news outlets and human rights advocates worldwide. However, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs released its statement much later on 21st August with an inaccurate date of disappearance.

Statements have been made on 20th August regarding Rilwan’s disappearance by international bodies such as UN Human Rights Commissioner, and media associations such as Reporters Without Borders, CPJ, IFJ and South Asia Media Solidarity Network on 19th August, as well as news outlets and human rights advocates worldwide. However, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs released its statement much later on 21st August with an inaccurate date of disappearance.

On 4th August, Rilwan tweeted from his Twitter account @moyameehaa: “on multiple occasions #Maldives’ journalists have said they don’t feel safe covering news related to gangs and Islamists”. Islamic Ministry has publicly tweeted distancing itself from the Islamic State (formerly known as “Islamic State for Iraq and the Levant”). Despite this, the government seems to be allowing violent groups to usurp executive power . No matter how much authorities step up search and seizure efforts now, it will not undo perceptions regarding consequences of the delayed reaction, or government’s abject disregard for public safety, equally for all citizens. And when the criminal justice system remains inept to dispense evidence-based justice – without relying solely on confessions – it fails to reassure citizens on escalating politico-religious gang violence.

Among many Maldivians like Rilwan online, the mysterious disappearance of a levelheaded, humorous and well-read individual on social media produces a state of fear. Perhaps the government is suggesting that gang members and Islamist radicals affiliated with politicians will continue to police outspoken Maldivians, and the government will continue with its indifference towards autocratic judiciary in transition, polarized identity politics, gang violence and Islamist radicalism in Maldivian society. When these factors remain brewing unhindered or sanctioned by the State, discourse on identity, culture and religion remain not with progressive thinkers like Rilwan, but with delinquents preaching hate in the name of nation and religion.

Among many Maldivians like Rilwan online, the mysterious disappearance of a levelheaded, humorous and well-read individual on social media produces a state of fear. Perhaps the government is suggesting that gang members and Islamist radicals affiliated with politicians will continue to police outspoken Maldivians, and the government will continue with its indifference towards autocratic judiciary in transition, polarized identity politics, gang violence and Islamist radicalism in Maldivian society. When these factors remain brewing unhindered or sanctioned by the State, discourse on identity, culture and religion remain not with progressive thinkers like Rilwan, but with delinquents preaching hate in the name of nation and religion.

*Moyameehaa means ‘madman’ in Dhivehi – explaining why he used this as a pseudonym, Rilwan told his friend Lucas Jaleel; “The one who speaks rationally will be considered a madman when living among an irrational people.”