Torture rears its ugly head in the Maldives … again

by Anonymous

The use of torture as a tool of citizen oppression is a hallmark of dictatorships. The past and recent histories of the Maldives have been defined by authoritarian rule with a flimsy façade of overt calmness and order. This belied the covert systemic use of torture in the country’s prisons, which has been documented over the years by torture survivor and late historian Ahmed Shafeeg and more recently, by citizen advocates and journalists.

Nevertheless, Maldives has made great strides to address the issue of torture in some ways. Maldives ratified the UN Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment and Punishment (CAT) on 20 April 2004. On 23 December 2013, law number 13/2013, the Anti-Torture Law made history as the first such legislation passed in the country. A recognition of this magnitude can only be considered a great leap forward to eliminate the practice of torture, a heinous crime which robs society of its most basic moral values of humanity and respect for human dignity. In its statement issued on the occasion of the International Day in Support of Victims of Torture on 26 June 2017, the United Nations said,

Torture seeks to annihilate the victim’s personality and denies the inherent dignity of the human being.[1]

One of the most important milestones a society can achieve in its fight to eliminate torture is to acknowledge its presence and move towards redress through a process of truth and reconciliation. With the shift in the political environment since the historic change of government in November 2008, a group of torture survivors formed the Torture Victims Association of Maldives (TVA) in January 2010[2]. The TVA, in collaboration with the UK based NGO Redress with a mandate to end torture and seek justice for survivors, painstakingly documented torture survivor testimonials across the country. The testimonies revealed incidents of torture between 1978 to 2008, which is the duration of former President Maumoon Abdul Gayyoom’s 30-year long authoritarian regime. Two years since its inauguration, on 6 February 2012, the TVA submitted a dossier of testimonials provided by survivors of torture in prison, to the then President Mohamed Nasheed. The President “assured that he would do everything possible to find justice for the torture victims through the powers vested on him by the Constitution.”[3] The following day, on 7 February 2012, President Nasheed was removed from office in a coup d’état.

As the political situation in the Maldives took a turn towards transitional chaos, the efforts of the TVA risked invisibility. However, the commitment of some members of the TVA and Redress ensured that the torture report entitled, This Is What I Wanted to Tell You, was successfully submitted to the 105th Session of the UN Human Rights Committee (HRC) held in Geneva in July 2012[4]. At this session, the Committee reviewed the Maldives State Report on the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). The HRC also reviewed a record number of reports of human rights violations from the Maldives, submitted by various non-governmental human rights organisations and institutions.[5]

In its Concluding Observations of the country review, the HRC raised concerns about “reported cases of torture and ill-treatment by Police and National Defence Forces that occurred in the State party prior to 2008 which have not all been investigated.”[6] The HRC recommended the Maldives to “take steps to combat torture and ill-treatment in its all [sic] forms and prohibit it in its legislation. The State party should consider setting up an independent commission of inquiry to investigate all human rights violations, including torture that took place in the State party prior to 2008 and provide compensation to the victims.”[7] The HRC’s recommendation to enact legislation to prohibit torture was met by the Maldives by the passage of the Anti-Torture Act in 2013, which is a welcome development.

However, five years on, other recommendations including the establishment of an independent commission of inquiry to investigate human rights violations remain pending. There has been no move to address the important requirement to provide redress to survivors of torture. As the words of one torture survivor conveys clearly, a critical component of pursuing redress is to help survivors achieve some semblance of reparation and justice.

This is what I wanted to tell you. That is what I have to say.

I have no problems if you use these stories of mine anywhere.

If they and if I get some justice, that would be good. [8]

Following the Maldives ratification of the Optional Protocol to the Convention Against Torture (OPCAT) in 2006, the Human Rights Commission of Maldives (HRCM) was assigned the mandate to prevent and investigate allegations of torture, as the appointed National Preventive Mechanism (NPM). Further, it has a mandate to investigate and report on allegations of torture, under the Anti-Torture Act of 2013. In 2015, the HRCM produced its second annual anti-torture report, which investigated 37 cases of torture allegations.[9] However, the HRCM reportedly faces a multitude of challenges to its work, including the gathering of evidence, limitations in law and procedural standards as well as availability of resources.[10] In 2016, news headlines about allegations of torture investigated by the HRCM provide no evident change to the status quo from the previous year, except that the number of cases had increased significantly from 54 to 65.[11] Worryingly, the latter report explained that the HRCM said “it found no evidence to back up allegations of torture because of a lack of medical evidence, eye witness testimony, and CCTV cameras at jails and detention centres.”[12] Notably, the TVA/Redress torture report was also submitted to the HRCM in 2012, although to date it is not known what action the Commission has taken about the contents of the report.

In this context, recent allegations of torture in detention in the Maldives is an extremely disturbing development. Available documentation from the HRCM shows that during 2011, the Commission produced and publicly shared a number of reports about its monitoring and abuse prevention efforts in several places of detention across the country. The effect this monitoring and information sharing had, was a sense of accountability and reassurance that torture and inhuman and degrading treatment were no longer happening in prisons. However, after 2011 the HRCM appears to have become notably opaque on matters relating to the mandate of the NPM, with a significant decline in monitoring visits and reports. Although the consistent production of the annual torture report is a welcome activity, the acute limitations of the Commission noted in those reports are cause for concern.

Allegations of torture of high profile political detainees have surfaced through their lawyers and families in recent years. In 2016, media sources reported torture allegations of detained social media political activist Ahmed Ashraf (a.k.a Shumba Gong). His lawyer alleged that his client was “forced to sit on the floor in handcuffs” while officers “alternately poured hot and ice-cold water on him.”[13] In a media environment where news sources are being penalised for covering dissenting views using draconian laws, media self-censorship is the reality. Despite this, news sources have been consistently reporting alleged denial of medical access and healthcare to high profile political detainee Ahmed Adeeb, which has been described by opposition MP and lawyer Ali Hussain, as unlawful.[14] In deeply politically divided Maldives, Ahmed Adeeb’s alleged ill-treatment by the authorities is met with mixed views by members of the public, which alarmingly include reactions of indifference and vengeful acceptance. Although the premise that all humans have rights is commonly understood in the Maldives, ideas of justice and equality before the law remain elusive, perhaps due to its systemic absence. The occurrence of any form of cruel, inhuman, degrading treatment or punishment in detention (when a person is already punished with loss of liberty) regardless of their crime, is an unacceptable social and civic standard in any society.

On 19 June 2017, further allegations of cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment of a detainee emerged where the family of a suspected offender in custody released a public statement describing acts of torture perpetrated against him [15]. These include allegations of being detained in a place not deemed lawful for detention; being forced to sit and look at a wall for two days; being put in a cell where a strong smell of sewage made breathing difficult and requests for help were ignored, and later ridiculed; sleep deprivation by being constantly woken and interrogated; and providing drinking water with an unknown substance added to it, all of which affected the conscious state and well-being of the detainee.[16]

On 26 June, the HRCM issued a press statement on the occasion of the International Day in Support of Victims of Torture.[17] In their statement, the Commission reiterated its mandate to address torture prevention and called on State authorities to strengthen their efforts to prevent torture. The Commission made no reference to the status of the long pending TVA/Redress torture report submitted to the UN HRC and the Commission itself, in 2012. There was no mention of any action by the Commission to achieve the recommendations to address torture, provided by the UN HRC in their Concluding Observations to the Maldives. Nor did the statement acknowledge the immediate, current allegations and related concerns in the public domain, shared by families and lawyers of detainees.

One of the recommendations of the TVA/Redress torture report is to “ensure that credible allegations of more recent violations of human rights are promptly, effectively and impartially investigated, that those responsible for wrongdoing are brought to account, and that victims are provided with reparation.” [18] Additional recommendations include ensuring that the HRCM, the Police and the courts “have sufficient independence and resources to effectively respond to allegations of torture … in line with their mandates.” [19] It is clear that nothing will change until the Maldivian State authorities collectively arrive at a point to embrace the civic duty to eliminate torture and uphold the inalienable right of every citizen to their inherent human dignity.

As the UN’s recent statement explains, torture results in “pervasive consequences” that “go beyond the isolated act on an individual; and can be transmitted through generations and lead to cycles of violence”.[20] Torture achieves nothing but the decay of humanity and the degradation of social cohesion. The practice of torture irrevocably erodes the humanity of the torturer and the victim. Its virulent effects spread across society as generations of Maldivians suffer in the cycle of violence it generates, directly and indirectly. The occurrence of torture in Maldivian prisons has always been known to the public. However, the most authoritative documentation of systemic torture was provided by the TVA/Redress torture report.

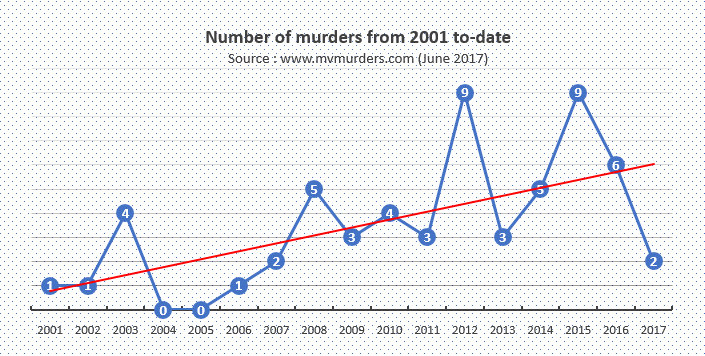

The inhumanity of torture does not remain forever confined within prison cells. The explosion of violence Maldivian society has been experiencing in recent years can be attributed to inhuman practices, impunity and the absence of accountability rooted within the country’s authoritarian governance system and structures. According to www.mvmurders.com the “Maldives has seen a steady increase in murders in recent times, to the point where the phenomenon is now a normalized part of Maldivian society.” The website is a response by concerned persons to document the issue of murder in an erstwhile calmer society where cases of murder rarely occurred. Starting from 2001, the website documents 58 murders to date. These include 2 toddlers, 8 minors, 30 young people between 18 to 30 years, 6 people between 30 to 50 years, 8 elders between 50 to 80 years and 4 of unknown age. Among these, 12% are female and 88% are male.[21] These figures do not reflect the criminal violence that take place due to gang fights or violence against women and children, which also result in grievous physical and psychological long-term harm to victims.

The legacy of systemic violence, impunity and the persistent practice of torture in the Maldives undoubtedly converge to bring society to its current reality of insensitivity, inhumanity and insecurity. The ineffectiveness of responsible authorities to address the issue remains a fundamental obstruction to begin to rid Maldivian society of the plague of torture.

[1] International Day in Support of Victims of Torture, 26 June, UN, http://www.un.org/en/events/torturevictimsday/

[2] Pain and Politics : Torture Victims Association inaugurated, Minivan News, 21 March 2017, https://minivannewsarchive.com/tag/torture-victims-association

[3] Torture Victims Association calls on the President to help find justice, 06 February 2012, President’s Office, http://www.presidencymaldives.gov.mv/?lid=11&dcid=6722

[4] This Is What I Wanted To Tell You : addressing the legacy of torture and ill-treatment in the Maldives, TVA/Redress, July 2012, http://www.redress.org/downloads/country-reports/1206_maldivesreport.pdf

[5] Centre for Civil and Political Rights (CCPR Centre), Maldives NGO review reports 2012, http://ccprcentre.org/country/maldives

[6] Maldives – Concluding Observations adopted by the Human Rights Committee at its 105th session, 9-27 July 2012, CCPR/C/MDV/CO/1, 31 August 2012, http://ccprcentre.org/doc/2012/07/G1245583.pdf

[7] ibid

[8] This Is What I Wanted To Tell You : addressing the legacy of torture and ill-treatment in the Maldives, TVA/Redress, July 2012, http://www.redress.org/downloads/country-reports/1206_maldivesreport.pdf

[9] 54 cases of torture filed against police, Maldives Independent, 01 August 2015, http://maldivesindependent.com/crime-2/54-cases-of-torture-filed-against-police-115980

[10] ibid

[11] Watchdog lets police off the hook over torture claims, Maldives Independent, 03 August 2016, http://maldivesindependent.com/politics/watchdog-lets-prison-guards-and-police-off-the-hook-over-torture-claims-125885

[12] Ibid (emphasis added)

[13] Shumba Gong tortured in jail, says lawyer, Maldives Independent, 10 April 2016, http://maldivesindependent.com/politics/ashraf-tortured-in-jail-says-lawyer-123422

[14] Obstructing Adeeb’s access to medical care is unlawful : Ali Hussain [translation from Dhivehi], VFP, 21 June 2017, https://vfp.mv/f/?id=61956

[15] Statement published via Twitter by family member Maumoon Hameed, @maanhameed, 19 June 2017, https://twitter.com/maanhameed/status/876718581257347072

[16] Ibid [translated from Dhivehi]

[17] HRCM Press Statement on the occasion of the UN International Day in Support of Victims of Torture, 26 June 2017, HRCM, http://hrcm.org.mv/dhivehi/news/page.aspx?id=650

[18] This Is What I Wanted To Tell You : addressing the legacy of torture and ill-treatment in the Maldives, TVA/Redress, July 2012, page.2, http://www.redress.org/downloads/country-reports/1206_maldivesreport.pdf

[19] ibid

[20] International Day in Support of Victims of Torture, 26 June, UN, http://www.un.org/en/events/torturevictimsday/

[21] Data source : www.mvmurders.com (June 2017)