Violence in the Maldivian family: why does it continue to breed despite the Domestic Violence Prevention Act?

by H Abdulghafoor

Four years ago today, on 23 April 2012, the historic Domestic Violence Prevention Act (DVPA) entered the legal framework of the Maldives. The legislation gave some hope to those advocating preventing domestic violence and gender based violence, which according to available research affect 1 in 3 women in the country at some point in their lives.

Article 34 of the 2008 Constitution of the Maldives provides the fundamental right to every individual to marry and establish a family. It further says that,

The family, being the natural and fundamental unit of society, is entitled to special protection by society and the State.

The DVPA 2012 is among several laws that are intended to provide protection to the most vulnerable in society. It is the only law that specifically works to protect families from the social affliction of violence occurring within families. However, as the old cliché goes, you can take a horse to water but you cannot make it drink.

The family is indeed the fundamental unit of society. It is also where a significant number of the women who are primary carers of children and the elderly (not to mention the men), experience violence in all its forms – physically, psychologically and economically. The primary perpetrators of violence, as research tells us, are disproportionately men. Husbands, fathers, stepfathers and uncles are most common among perpetrators of domestic abuse.

The primary purpose of the DVPA 2012 is to criminalise domestic violence. The law further seeks to do a wide range of things. These include –

providing protection to victims of domestic violence;

to find justice for victims;

to prevent violence and rehabilitate perpetrators;

to increase stakeholder awareness about domestic violence to increase their competency to address the issue;

to identify civil and criminal liabilities of offenders and also,

to “comply with international standards for the prevention of domestic violence and to apply and enforce relevant principles of justice in accordance with such standards”.

The DVPA 2012 provides a comprehensive definition of what a “domestic relationship” is, clarifying the circumstances in which the law is applicable. These include connection through marriage, sharing the same residence, being related through parenthood or guardianship, connection through domestic service as well as those in an intimate relationship. In the Maldives, research has shown that 1 in 5 women experience physical or sexual violence from an intimate partner. Intimate partner violence is a debilitating form of violence from which many women are unable to escape. A vivid case in point among recent incidents is the sickening and brutal fatal assault by an estranged husband against his wife in Gaaf Dhaal Thinadhoo in December 2015.

The DVPA specifies 17 different acts of domestic violence ranging from physical and psychological violence to economic deprivation and property damage. Intimidation, harassment, stalking, coercion, confinement without consent, enforced impregnation to deter spousal separation as well as exposing a minor to acts of domestic violence are among notable acts criminalised by the law. However, the extent to which these definitions are helping to reach convictions or to apprehend perpetrators of abuse is questionable.

The Family Protection Authority (FPA) is an independent entity created by the DVPA. While Article 68 of the law says that the law will come into force with immediate effect upon publication in the Government Gazette, it took the government nearly six months to physically establish the FPA – and even then, on a shoestring. The Authority has yet to become fully functionally effective, being under-staffed and significantly under-funded, which is a pervasive issue afflicting the social services sector in the Maldives. In its initial few years, the FPA’s programming work was almost entirely funded by external donors such as UN agencies. For a country as rich with tourism dollars as the Maldives, it is a telling indicator of poor prioritisation and weak governance that the Maldivian State is unable to provide “special protection” to the family as the Constitution demands.

It is uncommon in the Maldives for laws to highlight the necessity for budgetary allocation. However, Article 55 of the DVPA specifically instructs the People’s Majlis to ensure that adequate funding is provided to implement the law by providing the necessary resources to relevant authorities such as the FPA and the police services. Nevertheless, the failure of the People’s Majlis and the government to uphold the law is amply evident in the resource-poor state of the FPA. In 2014, the FPA requested a budget of MVR 9.9 million of which MVR 2.3 million was facilitated. In 2015, the FPA applied for a budget of MVR 8.1 million of which MVR 4.6 million was facilitated. However, the authority was only able to expend 85% of its 2015 allocation due to government imposed restrictions on its expenditure.

As the oversight authority to ensure the implementation of the law, the FPA is assigned a sweeping mandate under Articles 52 and 53 of the DVPA. Despite minimal resources, the FPA has managed to exist and remain a credible entity due to the commitment of the team of young staff at the Authority, who are assisted by a supportive Board. The challenges faced by the FPA are vastly disproportionate to the level of State support the Authority receives. In its 2015 Annual Report, the FPA observed the following challenges to its work:

challenges to implement its mandate to raise public awareness due to inadequate resources including staff and funding

challenges to provide the necessary services to victims of violence and support them to productively participate in society due to lack of technical expertise

challenges to provide counselling services to support perpetrator rehabilitation due to lack of technical expertise.

FPA reports that in 2015, a total of 438 cases of domestic violence were reported to the Authority. These include 352 cases against women, 122 cases against men and 2 cases against the unborn child. What is clearly evident is that each year, the number of cases reported to the FPA has increased dramatically, from 19 cases in 2013, to 149 cases in 2014 to 438 cases in 2015. The inability of the government to provide resources to the FPA is indicative of a policy level disconnect with the reality of the prevalence of domestic violence in the Maldives.

Another sobering reality is that domestic violence cases rarely reach prosecution stage following investigation. One of the biggest challenges for prosecution is that victims of abuse often retract their statements after lodging complaints. They often do not want to pursue their claim for complex reasons, sometimes due to family situation and sensitivity to associated social stigma; economic dependency on the perpetrator; fear of reprisal as well as lack of confidence in the available protection services. In the Women’s Vision Report produced by UNDP in 2014, close to 75 percent of respondents rated domestic violence as their topmost personal concern from a list of twelve issues. Fourth on the list, with 56 percent was the challenge of accessing justice.

In May 2015, the criminal court fined a man MVR 200.00 (USD 13.00) for assaulting his wife and inflicting grievous bodily harm. To put this in perspective, the fine for a first time parking offence in Malé currently stands at MVR 250.00 (USD 16.00). At that time, domestic violence cases were being prosecuted using the old Penal Code of 1966, an obsolete law which has now been superseded by the new Penal Code which came into force in July 2015. Domestic violence issues do not take a linear route and prosecution of cases depends on several factors. The DVPA is fundamentally a law designed to prevent the occurrence of domestic violence and some would consider it a shortcoming of the law that it does not dwell on punitive measures. However, Article 35 of the DVPA specifies fines for persons who breach the conditions of Protections Orders, with a first time offence carrying a six month jail sentence or a fine not exceeding MVR 15,000.00. This cumulatively increases to three or more offences, carrying a three year jail sentence or a fine not exceeding MVR 50,000.00. Whether this clause of the DVPA has ever been used is not known at the time of writing. With the arrival of the new Penal Code, it is anticipated that prosecution is better equipped to seek just remedies for victims of domestic violence through the courts. It is once again, a weakness in the system that data is not available in the public domain on case prosecution of domestic violence incidents specifically.

The DVPA entrusts a duty of care to healthcare professionals to report suspected cases of domestic violence. However, it is notable that some doctors observe that this requirement is in conflict with their professional requirement to protect patient confidentiality. Such attitudes indicate a lack of understanding by health professionals of the law, its intent and the much broader problem domestic violence is in Maldivian society. FPA reports that in 2014, there were no reported cases of domestic violence to the Authority, from the largest tertiary hospital in Maldives, the Indhira Gandhi Memorial Hospital (IGMH) in Malé. In 2015, the IGMH reported just 2 cases to the FPA. This is despite the fact that the vast majority of cases, a striking 66% of cases reported to the FPA in 2015, are from Malé.

The picture is the same with other health service providers. In order to address this knowledge gap among health professionals and health service providers, efforts are being made by the Health Protection Authority to inform and educate the health sector about their legal responsibility to respond to the issue of domestic violence. A compounding factor is the belief in Maldivian society, which clearly affects the behaviour of health professionals too, that violence against women is acceptable and permissible as per certain religious beliefs held by individuals. The law however, does not tolerate violence in any circumstance and specifies that duty bearers within the police, healthcare providers and the courts among others, must act to prevent and stop domestic violence.

One of the most important violence prevention tools provided in the DVPA is the instruction to the courts to provide Protection Orders to prevent acts of domestic violence. Article 18(c) of the DVPA states that “the fundamental objective of a protection order is to ensure the physical and psychological protection of the victims or potential victims of domestic violence, and to ensure their health and rights are protected and preserved.” Nevertheless, in the 2014 Annual Report of the FPA, the authority observed that most magistrates’ courts in the country do not have the form to issue a protection order. Such basic administrative short-comings malign the implementation of this important law to families, constitutionally entitled to “special protection by society and the State”.

A further barrier to the implementation of the DVPA is the alleged reports by implementing stakeholders that in some cases, magistrates refuse to issue Protection Orders as they perceive it to be “un-Islamic”. It is a fundamental flaw in the judicial system when a judge is allowed to choose which article of which law to apply at whim, based on personal beliefs. According to FPA, a total of six Protection Orders were issued in 2013, 12 in 2014 and 15 in 2015 in the entire country. The vast majority of these orders were issued by the Family Court in Malé. In the magistrates’ courts, a total of four Protection Orders were issued over this three year period. While the Protection Order is a critical component of the DVPA, the challenges to its implementation put women and families at risk of life-long trauma and entrapment in the cycle that domestic violence breeds.

The DVPA took time and effort to be brought into existence, to provide essential and worthy protections to safeguard the family. The law seeks to stop the dysfunction of violence happening within these fundamental building blocks of society. It seeks to break the cycle of violence afflicting families, often across generations. The will to fund and support the implementation of the law, however, is virtually non-existent. The reality of domestic violence in all its abhorrent forms runs insidiously in Maldivian society, frequently making disturbing news headlines. In many instances, mostly unreported, key stakeholders choose to dismiss the law, ignoring the professional and civic responsibility of its mandate, almost as though their individual beliefs can be held above the law. A system of accountability is yet to be established to ensure that law enforcement is adequately practiced by those mandated by the law. A system to ensure the effective implementation of the DVPA to protect the fundamental unit of society is taking far too long in becoming a reality, four years into its ratification.

The situation leaves room to say that when it comes to preventing domestic violence in the Maldives, the proverbial horse has been taken to the water. It simply refuses to drink.

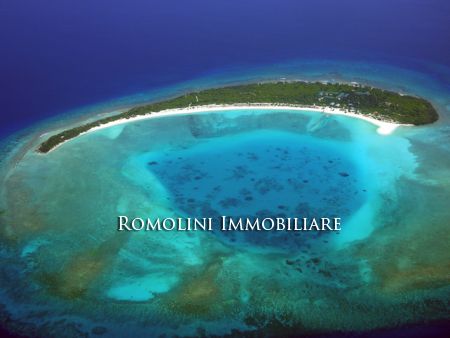

The only natural resources the Maldives has—born of its fragile environment of immense beauty—are being sold rapidly. Reefs, coral gardens, surf spots, diving sites, lagoons, islands gone, bartered away, shut off to the people. The money gained from the sales have been siphoned off in millions, distributed in bundles of dollars, handed out by Adeeb and accepted with grabbing arms by greedy politicians who entered the Majlis on the people’s vote to rob them blind. The government accepts this money is gone from the MMPRC coffers, but has chosen to deal with the matter by saying “the buck stops at Adeeb”.

The only natural resources the Maldives has—born of its fragile environment of immense beauty—are being sold rapidly. Reefs, coral gardens, surf spots, diving sites, lagoons, islands gone, bartered away, shut off to the people. The money gained from the sales have been siphoned off in millions, distributed in bundles of dollars, handed out by Adeeb and accepted with grabbing arms by greedy politicians who entered the Majlis on the people’s vote to rob them blind. The government accepts this money is gone from the MMPRC coffers, but has chosen to deal with the matter by saying “the buck stops at Adeeb”. The Maldives Police Service is another institution the CoNI report highlighted. The MPS has been constantly deteriorating in service and function for the last four years. Their mutiny on 7 February, and the role it played in the change of power is well documented. As is their brutality on 8 February 2012, and on many occasions since.

The Maldives Police Service is another institution the CoNI report highlighted. The MPS has been constantly deteriorating in service and function for the last four years. Their mutiny on 7 February, and the role it played in the change of power is well documented. As is their brutality on 8 February 2012, and on many occasions since. At a time when the government should be reeling from not just the millions lost in the MMPRC loot, but also the possible US$900 million price tag on the

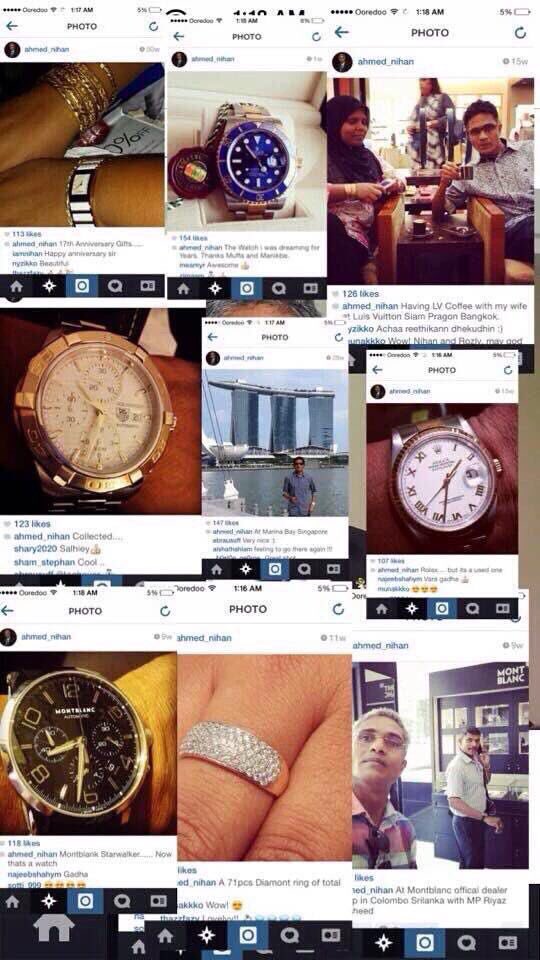

At a time when the government should be reeling from not just the millions lost in the MMPRC loot, but also the possible US$900 million price tag on the  Members of the higher-ranking officials put materialism at the forefront, buying people with cheap diversions and superfluous amusements while they open up the entire country, including its

Members of the higher-ranking officials put materialism at the forefront, buying people with cheap diversions and superfluous amusements while they open up the entire country, including its  The Maldives is going to be called up to the

The Maldives is going to be called up to the