48: 24 In and Out of Prison

by Azra Naseem

It was May 1991. On the small island of Dhoonidhoo, by the beach, stood a windowless corrugated iron shed 4ft wide, 6ft long, and 6ft high. During the day, the hot tropical sun beamed its rays directly onto the tin roof, making the air inside as hot as the inside of an oven on full blast. Under the moon, damp air from the sea wrapped itself around the shed, chilling the atmosphere within. Entrapped inside, in solitary confinement since November 1990, was a young man of 23 years. On 17 May 1991, exactly 24 years ago today, he turned 24.

Mohamed Nasheed, from G. Kenereege, Male’, had spent the previous year and a half inside the confines of the small shed. For 18 months his existence had been strictly controlled and designed to cause maximum pain and humiliation. He was allowed one shower a week. Everything he did had to be done inside the confines of the shed. His water was rationed – one litre every 24 hours for all his needs: drinking; cleaning; and ablutions.

The only ‘break’ from the relentless routine came when he was taken out for ‘interrogations’. Prior to each, he was allowed a bath and given a clean shirt to wear. All the sessions were videotaped. Instead of being asked questions, however, he was provided with a list of offences to which he was to ‘confess’: attempts to overthrow the government; inciting violence through distribution of subversive literature; concealing information on alleged anti-government terror plots; immorality; and un-Islamic behaviour.

His refusal to ‘confess’ resulted in a litany of punishments: his food was laced – sometimes with crushed glass, sometimes with laxatives, sometimes both at once. The laxatives caused diarrhoea; the glass cut him from within. It was a bloody combination, intended to cause optimum harm. At other times he was kept chained inside the shed; his water rations cut from one litre to half a litre every 24 hours. Once he was chained to a chair outside for 12 consecutive days, exposed to the elements; be it the merciless tropical sun or the ceaseless monsoon rains. He spent 14 days tied to a loud, throbbing electric generator, breathing in its fumes. For an entire week, he was subjected to sleep deprivation; allowed only 10-15 minutes’ sleep a night.

After 18 months of such inhumane treatment, on 8 April 1992, about a month before his 25th birthday, Nasheed was brought before a summary court and sentenced to three years and six months in prison. This time he was held captive on the island of Gaamaadhoo. Due to external pressure—mainly from the British government and Amnesty International—and changes in the domestic political landscape, Nasheed was released in June 1993, two years and four months before the end of his sentence.

By then he had spent another birthday, the third in a row, in jail. He was suffering from severe back pain, the result of police beatings in custody. He was bleeding internally, the result of food laced with crushed glass he had been forced to eat. He had just turned 26.

Journalism is a crime

Nasheed’s crime had been journalism. In the dictatorship of Maumoon Abdul Gayoom (1978-2008), where the State and its cronies tightly controlled all media output, Nasheed’s was the first voice that refused to be sweet-talked, bought, coerced, or threatened into silence.

On 24 January 1990, at the age of 22, Nasheed published the first issue of, Sangu, the first magazine to be openly critical of the regime in 12 years. It was banned almost immediately. Nasheed responded by publishing the very article, which the government had objected to most, in Sri Lanka’s The Island newspaper. For this, Nasheed was put under house arrest, the first of many times in which he would be deprived of his freedom. He doggedly persisted on his chosen path as a public watchdog, willingly meeting with foreign reporters in his house, including correspondents from the BBC and ABC (Australian Broadcasting Corporation) who, with Nasheed’s contributions, reported on the burgeoning political corruption and oppression in the Maldives. His 18 months of torture in Dhoonidhoo began the day after ABC broadcast its report.

There was more journalism, more writing, more threats, and more jail time to come. The next prison term was in November 1994 when he spent two weeks in solitary confinement for having written about yet more political arrests and repression by Gayoom. In February 1995 he spent another two weeks in prison where it was made clear to him that unless he stopped writing, he would be back behind bars yet again. Faced with the stark choice, he relinquished political journalism, and concentrated on writing longer, historical works.

In 1996 Nasheed published his first book, Dhagandu Dhahana, an account of the domestic affairs that culminated in Maldives becoming a British protectorate in 1887. Despite the book’s focus on history, he was ordered to have it removed from the shelves. He refused. Gayoom’s response was to charge him in relation to an article published two years previously, in November 1994. It was back to jail for another three months, then house arrest for a long period while his appeal was being considered, followed by another three months in jail. For the fourth time he was in captivity for his birthday. He had turned 29.

Free again in 1997, he stayed home to look after his first-born and write. His wife, Laila Ali, was the breadwinner. Writing under a pseudonym, he published Hithaa Hithuge Gulhun (A Connection of Hearts), a non-political novel. It became a best-seller.

Into politics

Nasheed’s first foray into politics was not pre-planned but initiated by Gayoom’s archrival, Ilyas Ibrahim, in October 1999, ahead of scheduled parliamentary elections. Hearing about a meeting between the two men, Gayoom had Nasheed’s house raided. Police took his computer along with several unpublished manuscripts. They were never returned. By then Nasheed had made up his mind to run for one of two seats as a Male’ Member of Parliament. He was successful. Two years later, after many efforts at reform as an MP, he was back in jail.

This time, the charge was theft. Among the documents police found when they raided his home in October 1999 was an old school notebook belonging to former President Ibrahim Nasir’s son. Nasheed picked it up from dumpster outside the Nasir residence which the government had emptied of all contents. Having been in school with the younger Nasir, the notebook, destined for the bin, was of sentimental value to Nasheed. Nevertheless, charged with theft—a Hadd crime in Shari’a—Nasheed was stripped of his parliament seat and sentenced to two years banishment to An’golhitheemu, an island with a population of just 30. After six months in virtual isolation on the island, he was transferred to house arrest. With pressure from Amnesty International, Reporters Sans Frontiers, the International Parliamentary Union (IPU), and other international bodies, he was free again after three months. By now it was August 2002, and Nasheed was 35.

A year of relative calm and more writing followed. Nasheed published two more books, Enme Jaleel, a historical novel, and Dhan’dikoshi, a genealogy of leading families in Male’. In English, he wrote two more, A Historical Overview of Dhivehi Polity 1800-1900, and Maldives in Armour: Internal Feuding and Anglo-Dhivehi Relations 1800-1900.

Trouble, and more jail time, was not far away. On 20 September 2003, the National Security Services (NSS), killed Evan Naseem, a young prisoner in Maafushi jail. Nasheed was instrumental in exposing Evan Naseem’s death for the murder that it was. He beseeched the examining doctor to deviate from what was then a standard procedure of signing prisoners’ death certificates without examining the body first. Naseem’s battered and bruised body, once examined by the doctor and seen by his family and the public, brought most of the public’s endurance of Gayoom’s regime to an end; and lit the fire of the Maldivian democracy movement that refuses to die to this day.

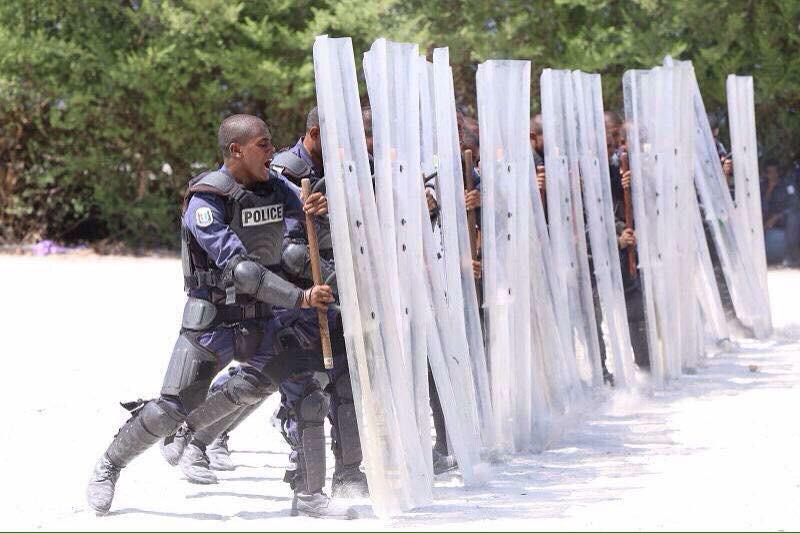

Much of what happened between then and now is well documented. The Maldivian Democratic Party (MDP) was declared as an entity in exile in Sri Lanka on 10 November 2003; Nasheed and several other close associates, in danger of losing their lives, sought asylum in the UK; and party leaders, members and activists continued their highly effective non-violent civil resistance actions in Male’. There were several heavy and brutal crackdowns, including the event now known as Black Friday on 12-13 August 2004 when the now infamous SO police brutally cracked down on thousands of protesters injuring hundreds and arresting 200.

Nasheed returned to the Maldives not long after, on 30 April 2005. Within a month—during which time he turned 38—he was back in Dhoonidhoo jail with several other MDP members and activists. This turned out to be a brief overnight stay, but it was not long before he was back in jail, dragged into custody from the Republic Square on 12 August 2005 where he was leading a mass gathering to mark the first anniversary of Black Friday. He remained in prison for about a week, then brought to court to face a battery of charges from inciting hatred against government and ‘creating fear in people’s hearts.’

Nasheed was back in jail—in solitary confinement—for the 80 days in which the ‘trial’ was held. It was followed by 324 days under house arrest. Mounting external pressure forced the government to withdraw the charges against Nasheed and release him on 21 September 2006. Another birthday had passed in captivity.

The freedom was short lived. Six months later, the people of Male’ were confronted with another dead body—another prisoner last seen alive in police custody. The body of Hussein Solah, carrying marks of torture was seen in the sea, near the remand prison where the police had held him. Large crowds gathered near the cemetery to view Solah’s body. Police dispersed the crowd brutally. They singled Nasheed out, pushed, shoved and beat him up, then dragged him into jail for another night. Released the next day, he left abroad to seek treatment.

Sweet but short

In November 2008 Nasheed became the first democratically elected leader of the Maldives. Both he, and the Maldivian people, experienced true freedom from tyranny for the first time in decades. Freedom of expression and assembly flourished. It was safe to speak, to criticise, to write, to draw, to feel, to debate, to dissent.

But, just like the many short-lived moments of liberty in Nasheed’s own history, this freedom for both him and the people was short lived. The beginning of its end came with the coup on 12 February 2012. In the year and nine months that followed, caretaker ‘President’ Mohamed Waheed Hassan Manik, genuflecting deeply, held the door open for the Gayoom family to return: to occupy the seats of power; shut the door on civil and political rights of the people; and to lock Nasheed away in prison. The new regime did not waste much time. Nasheed was back in Dhoonidhoo in October 2012, and again in March 2013. He was released on both occasions, pending a ‘trial’. On 13 March 2015, after what the entire world sees as a sham trial–charged and found guilty of ‘terrorism’ for the custody of a corrupt judge during his presidency–the regime threw Nasheed into jail yet again. This time to serve a 13-year sentence.

Today Mohamed Nasheed turns 48. It is the fifth birthday he marks in jail, 24 long years since he marked his first, 24th, birthday in jail back in 1991. And just as his fortunes have changed, so has the country’s. Counting the days behind bars today are many dissidents, critics and writers. Protesters as old as 70, and children under 18, are being brutally assaulted, pepper sprayed, arrested and tortured. Opposition leaders are being detained solely for being opposition leaders.

Once again, it is not safe to criticise the government; it is no longer allowed to freely assemble to peacefully protest without prior permission from the authorities; journalism is, once more, a crime. Journalist and writer Ahmed Rilwan was abducted in August 2014 and has been ‘disappeared’. Several prominent social media critics were dragged into jail, picked up from anti-governments protests like baitfish in a drag net. Dozens of Twitter users were detained for days and held in inhumane conditions. Some have been released, others like Shafeeu and blogger, Yameen Rasheed, remain in custody for no other reason except for their dissenting voices.

The trajectory of Nasheed’s life and that of the Maldivian democracy movement are closely intertwined. Every birthday he marks in jail marks another year in which the country’s struggle for democracy remains under captivity. Without Nasheed’s freedom, there would be no freedom for the majority agitating for a government of the people by the people–they are bound together, like ‘a connection of hearts’.