The daily pain

by Azra Naseem

Yameen Rasheed was brutally murdered a year ago today. He had just turned 29, was on the cusp of a major career breakthrough, and had, only a short while previously, met the love of his life. He was the pride of his parents, a beloved brother, a doted upon uncle, a precious friend, an admired colleague, and a brave social critic. The promise of a fulfilling life of success, love, and potential contributions to shaping a more tolerant Maldivian society brought to an abrupt end by a knife plunged frantically into his young body; hatred cancelling out love, intolerance victorious over empathy.

It would have come as no surprise to Yameen that in the long painful year that has passed since his life was taken, none responsible have been punished. Justice, as he well knew, is non-existent in the Maldives. And nothing has highlighted this truth more than the obstacles against punishment for Yameen’s killers. To begin with, the investigation was so deliberately careless his already traumatised family had to sue the police for negligence. Their case, of course, was thrown out. The ‘trial’ that followed, and is said to be ongoing, is so secret it is closed even to Yameen’s family.

Murders are not just personal crimes, but crimes against society; but society is kept in total darkness about this particular killing which—if only society were to indulge in a moment of collective reflection it would realise—is a pivotal event in its history.

If Yameen’s death goes unpunished there would be no turning back for Maldives.

What is happening behind closed doors in the name of justice for Yameen is a struggle for the direction Maldives will take in the future: will it embrace tolerance, or will it submit to religious puritans free to take the lives of those who fail their demands for absolute conformity?

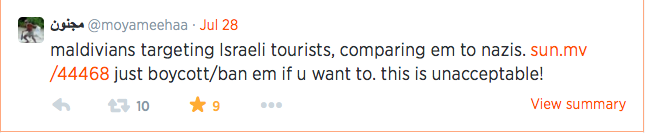

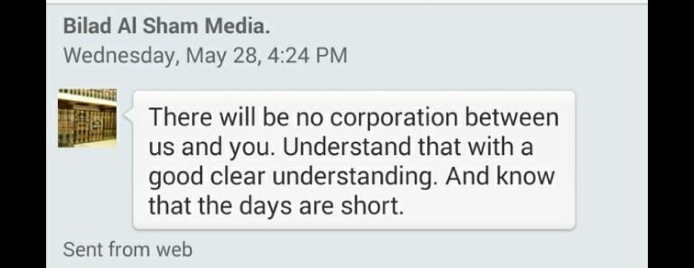

Yameen’s killing was followed by a flurry of state activity. Not against extremists who assume the authority to murder whomever they think offended what they believe is the right way to practice Islam, but against those who expressed views of Islam contrary to the extremists’ interpretations. The president used the occasion to mount an attack on ‘those who mock Islam’, and self-proclaimed religious authorities tripped over themselves to defend the right of the killers to take the lives of those who advocate tolerance. An Islamic society cannot be secular. It cannot allow other religions to co-exist. Muslims cannot empathise with people of any other faith. To advocate tolerance is to mock Islam. The message that has been broadcast loud and clear—by the president in his various speeches; by religious leaders; by figureheads of the various sects of Islam that have established themselves within Maldivian society; and—sadly—by a substantial portion of the population itself, is: follow this script, or be excluded from Maldivian society. And from life itself.

Around the world, across space and time, seemingly isolated events have triggered dramatic changes in societies. The killing of Arch Duke Ferdinand in 1914 became the catalyst for the First World War. Almost a century later, the self-immolation of Mohamed Bouazizi in December 2010 became the catalyst for the revolution in Tunisia, which gave birth to the ‘Arab Spring’.

The killing of Yameen on 23 April 2017 had the potential to trigger similarly dramatic changes in Maldivian society. It was an event that could have— should have—brought every mother, daughter, sister, brother, friend, son, and fellow citizen out on to the streets from Male’ to Addu and everywhere in-between. It should have incensed every Maldivian who believe in the sanctity of life, who hold dear the tolerance preached by their faith, who value the existential right of human beings to think freely.

But the moment passed, only those personally touched by Yameen’s wonderful spirit came out on the streets. A handful of ‘society at large’ came too. But a year later, they too, have dwindled in number to almost nothing. Only family and friends, and a core group of human rights defenders, remain on the streets. Their pain is as fresh as it was this day a year ago, their demands as sincere, their commitment to justice for Yameen unwavering.

But they cannot do it alone.

Whether people realise it or not, Yameen’s death is a life-changing event for them. By not raising their voices as one, by remaining silent in the face of the farce that is ‘justice’ for Yameen, by going about daily business as if nothing has changed, in the empty space created by their silence, they are allowing religious puritans to write their own futures, and the futures of their children.

Perhaps none of this would have surprised Yameen.

But it would have certainly caused him pain.

It would have caused him pain to know that the society he fought for did not fight back for him; that when he lost his life in the battle for freedom, the war had already been lost to those making freedom a crime.

Or has it?

Without a people’s uprising or a similarly obvious consequence, Yameen’s killing may not seem as life-changing a moment in the history of the Maldives. But it is. In retrospective, if society remains complicit as now, it would be pointed to as the event which planted Maldives firmly on the path to intolerant religious puritanism. Truth is, there is still time to shape what happens next. The ‘trial’ is not over yet. The future is not yet writ large in a ‘court’ verdict. The people still have the power to make sure it will be one that allows all Maldivians right to think freely for themselves without being punished and killed for what they think and what they say.

What it will take is for everyone who believes in such a society to stand up.

Like Yameen did.

Or be prepared for daily panic, and endless pain.

Ahmed Rizwan Abdulla, a Maldivian journalist, blogger and human rights advocate, is missing. The 28-year-old was last seen by his family on 7 August. Unlike most Maldivians of his age, Rizwan does not live with his family but rents an apartment in Hulhumale’, a 20-minute ferry ride from Male’ the capital. Rizwan is a deeply spiritual person, known to enjoy solitude. It is not unheard of for him to take time off from society to indulge in the right to be left alone. His close friends know that. This time, however, is different.

Ahmed Rizwan Abdulla, a Maldivian journalist, blogger and human rights advocate, is missing. The 28-year-old was last seen by his family on 7 August. Unlike most Maldivians of his age, Rizwan does not live with his family but rents an apartment in Hulhumale’, a 20-minute ferry ride from Male’ the capital. Rizwan is a deeply spiritual person, known to enjoy solitude. It is not unheard of for him to take time off from society to indulge in the right to be left alone. His close friends know that. This time, however, is different.