Bingaa: a case for intellectual leadership on Maldivian affairs

As I write, former Maldives National University Chancellor, scholar and 2013 MDP Vice-Presidential candidate Dr Mustafa Lutfi has been arrested following May Day 2015. In his book School Curriculum and Education of Maldives, which is based on his doctoral thesis, Lutfi critiques the various forces that have shaped the country’s education system. It was a book he gifted to Maldives National University Library in 2011. Adding to literature on the Maldives’ recent political history is Aishath Velezinee’s book The Failed Silent Coup: In Defeat They Reached for the Gun. The author offers a first-hand account of (alleged) corruption during her time as a member of the Maldives Judicial Services Commission from 2009 to 2011, circumstances that ultimately led her to become a whistleblower. Velezinee says, like Lufti, she offered to donate her book to the University library. However, her offer was turned down.

The relationship between intellectual activity and democracy ought to be one that enhances the public sphere. But how can scholarship contribute to this goal and flourish in a social and political environment that discourages rigorous, informed debate? In this essay I explore the idea that deficient or suppressed intellectual activity diminishes the quality of democracy; and, that a lack of critical inquiry equates to increased mobility for state operators when their policies are unchecked by engaged analytical minds. Although not exhaustive, I convey a literature review of scholarly and non-scholarly articles to articulate potential future directions for research on the political history of the Maldives. Peer-reviewed research is severely lacking in this area. Yet scholarship offers significant potential in terms of unpacking the consequences of political authority and informing responses to it.

Media narrative & international representations of the Maldives

Media have attempted to fill the knowledge gap vacated by scholarship. The narrative adopted by international media about the policies and practices of the second Gayoom regime (2013-today) is typically twofold. The first is captured in the depiction of the regime offered by Amal Clooney who, writing in The Guardian, opens with: “It may be famous for the pristine holiday beaches of its Indian Ocean coastline but the Maldives has taken a dark authoritarian turn.” The bundled imagery channels international readers’ existing knowledge of global tourist branding, suggesting simply: yesterday the Maldives was pristine, peaceful and sunny; today it is dark, evil and despotic.

The media narrative then tends to depict outrage at this “turn” and portrays the Maldives as democratically deficient. As Jose Ramos-Horta and Benedict Rogers’ write in The Guardian in relation to Nasheed’s sentencing: “On Friday night the final nails were hammered into the coffin of democracy in the Maldives.” It is thus not surprising that for many commentators the recent history of the tropical island state symbolizes a betrayal of values regarded by the international community to be inviolable such as democracy, transparency and human rights. In media discourse the country is also increasingly associated with a lack of press freedom and as a recruiting ground for Islamic State militants. These factors lend to a growing perception that the Maldives is tinkering on being a failed state and lend weight to advisory warnings to foreign tourists.

To draw on a local phrase, the bingaa (Dhivehi for ‘foundation slate’) of the ruling regime appears in international media coverage to comprise force, fear, money, intrigue, hard-line hostility to the opinions of foreign dignitaries, and a militaristic defense of sovereignty in place of heeding international condemnation of judicial and other shortcomings in due process. On this point it is worth mentioning how another media text – The Island President – may have contributed to these portrayals as a mode of “backgrounding”. Responding in The Guardian to the incarceration of former Maldives President Mohamed Nasheed, his lawyer Amal Clooney refers to The Island President, which introduces viewers to some crucial political history regarding the first Gayoom regime (1978-2008). Clooney says Nasheed’s “remarkable story is chronicled in the acclaimed documentary”.

However, as an explanation of Nasheed’s imprisonment for 13 years on “terrorism” charges in the current political climate, his legal case needs to be put into greater context. As a case study, scholars are yet to unpack the internationally acclaimed film as a media/discursive text, the geo-political circumstances in which its subjects gained international notoriety, its success as a vehicle for the reproduction of ideologies and beliefs, and the extent to which it has shaped diplomatic and other commentators’ views on the subject of Maldivian politics.

Knowledge capacities & organization of the state

Grievances highlighted by both last week’s May Day protests and Nasheed’s imprisonment have revealed the need for greater understandings of the strategic, discursive and institutionalized hold on political power by the second Gayoom presidential regime. Ideally this would begin with an exploration of similar processes pertaining to the first Gayoom presidential regime and through identifying continuities and departures in each of these approaches to government. Moreover, through rigorous research and critique scholars can identify processes delivering opportunities including “Corruption, closed-door decisions, ‘jobs-for-the-boys’, pork-barrelling, being ignored by your [elected representatives], and, among other scurvy possibilities, shifting the fruits of the many to the few.”

The political currency of unchallenged historical knowledge concerning Maldivian statehood is significant. To exemplify these implications, the gap in scrutiny has had measurable impacts on the conduct of political life, embodied in the unqualified privilege – by international standards, that is – acquired by the three Criminal Court judges who heard Nasheed’s terrorism trial. None of the judges have law degrees. This deficiency has a functional role for the second Gayoom regime whose uncompromising policy platform requires generating electoral buy-in for reviving a quasi patron-client system that casts privilege on supporters, power to the wealthy and exile to detractors.

We can see how the function of knowledge deficiency plays out in the regime’s politicking; last week Maldives Foreign Minister Dunya Maumoon described the Presidency of Nasheed as “the single most brutal, dictatorial and violent period of rule in contemporary Maldivian history.” Being up close and personal to the subject matter her entire life – as daughter of 30-year autocratic ruler Maumoon Gayoom – Dunya’s grasp on Maldivian history may be, in her perspective, correct. And therein lies the problem. The role of scholars here is to critique her objectivity and assess the propaganda value of these statements. Moreover, any claims democratic governments make about history requires inquisitive dissection and fact-checking.

The myths, linguistic capital and political folklore surrounding political elites requires critical analysis and contextualisation. This includes unpacking how myth, image and symbols lend to cultivating power as well as popular tropes concerning the leaders themselves – take, for instance, the implications of networked information flows viz-a-viz ‘Anni’s lucky number’ (being 4) for the democracy movement, or why the Progressive Party of the Maldives chose the colour pink (some say because of the national pink rose). Furthermore this includes analysing literary overtures accompanying the first Gayoom regime such as Royston Ellis’ A Man for All Islands: A Biography of Maumoon Abdul Gayoom. There are also two self-authored books by Maumoon Gayoom, The Maldives: A Nation in Peril (1998) and Paradise Drowning (2008) – both showcasing the former president’s orations on environmental challenges facing the Maldives.

Interestingly, while scholarly contributions to public debate are limited, intellectuals have been mobilized within the bureaucratic power structure of the Maldives under the current government. One outcome of the 2013 elections that delivered Yameen Abdul Gayoom the presidency is the delegation of Ministries to at least four highly educated political actors whose names are preceded by the title ‘Dr’. Critics suggest these appointments lend an air of prestige and respectability to a government losing the ideas contest. It may also capture a lingering deference to formality and titles within the Maldives’ political hierarchy, which is as much a cultural as it is an historical phenomenon. Collectively these Ministers have doctoral expertise in marine offshore aquiculture, civil engineering, and sharia law. My own consultations revealed that greater expertise is sought in foreign affairs, legal and judicial matters, public service, public policy, transparency, public health, communications, media and advocacy.

Intellectual vanguard

Without more methodical critique of the past, Maldivian democracy will continue to endure a wilderness of intrigue. Maldivians have expressed desires for greater knowledge about their country’s politics, parties and leaders. Many stated they want the country to have a firmer grip on its dealings with the international community, especially “big” countries like India, the US and China. Questions concerning the lack of knowledge and political biography are entwined with global trends and the necessity to respond to international actors. Knowing more about topics like foreign policy and what makes good public policy is about making an investment into national development, regional stability and social cohesiveness.

All but a handful of related and semi-related studies explore the politics of tourism (the Maldives’ “golden goose”), international relations, regional security strategy, legal interpretations of Maldivian politics, and the implications of economic transition and sustainability for the country. A proactive intellectual vanguard is crucial as much for consensus building as it is to initiating change. The importance of intellectuals as contributors to political change is emphasized in Gramsci’s efforts to accentuate the centrality of the “war of position” (the contest of ideas, values, the cultivation of collective memory and the formation of an “historic bloc”), to be waged in conjunction with a “war of maneuver” (waged through force and economic means). (Gramsci of course was referring to “organic intellectuals” – producers of knowledge articulating a cause from within – but I’ll leave that for another time.)

Yet there remain few peer-reviewed accounts of the contemporary political history of the Maldives and crucially histories ‘from below’ incorporating the impacts of civil society, institutions, cultural life and religion on democracy. One exception is the ongoing series of critical essays published via Dhivehisitee: Life and Times of Radicalisation & Regression Maldives authored mainly by Maldivian Dr Azra Naseem, who, while publishing in a non-academic outlet, is among the most critically engaged with the subject matter. Furthermore, Maldivian scholar Dr Athualla Rasheed has written several academic journal articles, but only with noticeable caution does he define President Nasheed’s resignation/ousting as the ‘pre and post–coup periods’.

And it is a hesitance worth unpacking. President Nasheed stepped down from power in February 2012 following what international commentators, like Clooney, have labeled a “coup” at military gunpoint. By contrast Nasheed’s successor and political opponents have defined this episode in smoother terms as a legal “transfer of power”, a position supported by the Commonwealth-backed Commission of National Inquiry (CoNI). Despite this, evidenced by public discourse is that continuing tension over how to define this moment lays at the heart of the struggle for democratic reform in the Maldives today. For Maldivian analysts, permitting ambiguity to define this moment is understandable and symptomatic of the pressures faced by autocratic subjects to refrain from ‘rocking the boat’.

By contrast international scholarly commentators have been at liberty to describe the event as a coup in solidarity with Maldivian democracy activists. For instance, in their essay on Dhivehisitee, Professor John Foran and PhD researcher Summer Gray (September 2013) issue little restraint utilizing the term “coup”. They support this view in Counterpunch, stating: “Two independent legal evaluations of the CoNI Report both unequivocally found the Report deficient”. Notwithstanding their extensive citation of supporting empirical materials, there is significant room to get the ball rolling towards producing some foundational peer-reviewed analysis on the subject matter.

Harnessing future knowledges

Through knowledge creation, research and a commitment to learning commentators may draw firmer conclusions about the history, and perhaps the future, of Maldivian democracy. This is particularly with regards to the various ways in which – as many commentators suggest – the second Gayoom regime has consolidated power, limited dissent, stacked the judiciary, maintained a contested human rights record, goaded opposition supporters into violent confrontations and mobilized security forces in response to May Day protests.

Enter: J.J. Robinson’s forthcoming book The Maldives: Islamic Republic, Tropical Autocracy (to be released in October in the UK and November in the US) which observes the thrusts of Maldivian democracy from the author’s perspective as former editor of Minivan News. Robinson describes the book as “a journalistic account of the Maldivian democracy experiment” with a particular focus on the role of judiciary, and makes the case that “the unconstitutional reappointment of Gayoom’s pet judiciary in August 2010 was the thing that really scuttled any hope of a stable democratic outcome.” Robinson’s account is to be the first ‘embedded’ narration of political change in contemporary Maldives (that is, at least by a non-national).

This contribution to public knowledge is set to be powerful, up close and engaging, and an example of why more of analytical knowledge is needed regarding the political history of the Maldives. Critique, ideas, knowledge creation, debate and intellectual leadership are vital for informing political change in the Maldives as well as international responses to the country’s looming political crisis.

While international media, the US, EU and India continue to convey outrage at the re-emergence of autocratic tendencies in the Maldives, little if anything is being delivered by the international community in terms of investments into capacity building intellectual culture and leadership. This is a shortcoming of international aid programs despite some countries like Australia facilitating education sector improvements since the days of the Nasheed administration.

Meanwhile, Velezinee, who began her PhD candidature at Erasmus University in 2015, says she hopes the Maldives “moves towards scholarly debates with a view to establishing the rule of law and a democratic culture.” The difficulty, she points out, is that “the subject matter means it is taboo for any public institution in the Maldives to be viewed implicitly or explicitly to act as a conduit towards learning about these events in any way, shape or form.” Velezinee adds: “Currently, all debate is left to politics and politicians, and the only ‘scholars’ engaging appear to be religious scholars with their own interests. We have to change the language of political debates.”

Optimistically, Maldivian researchers are dispersed all over the world. Away from home they are slowly beginning to piece together their political history. Perhaps the time has come to harness this network and undertake a more proactive dialogue between scholars interested in developing a political biography of the Maldives.

Non-peer reviewed academic resources of note

Colton, Elizabeth, ‘The Elite of the Maldives: Sociopolitical Organisation and Change’ (PhD Thesis), London School of Economics and Political Science, University of London, 1995. URL: http://etheses.lse.ac.uk/1396/

Jorys, Shirley, ‘Muslim by Law – A Right of a Violation of Rights? A Study About the Maldives’ (Thesis), 2005. URL: http://ebookbrowse.com/shirley-jorys-dissertation-muslim-by-law-pdf-d214056909

Mohamed, Mizna, ‘Changing reef values: an inquiry into the use, management and governances of reef resources in island communities of the Maldives’ (PhD Thesis), University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand, October 2012.

Zahir, Azim, ‘Islam and Democracy: The Maldives Case Study’ (Masters Thesis), Master of Human Rights, University of Sydney, 2011.

Dr Robert Carr produced the Maldives National University Political Science Curriculum. He is a researcher at University of Western Sydney. Tweet: @robcarr09

Photo of standoff between pro-democracy supporters and the Maldives Police Service on 1 May, by Dhahau Naseem

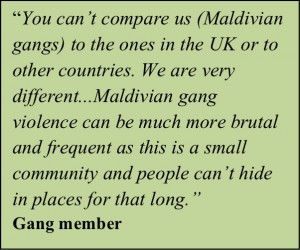

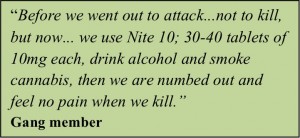

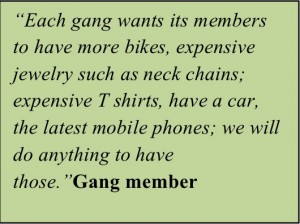

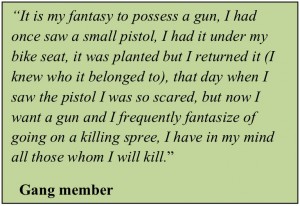

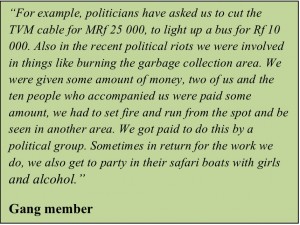

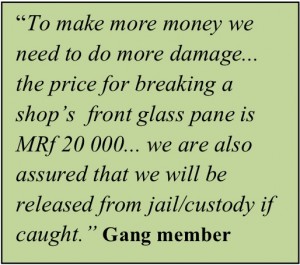

The public alliance of Defence Minister Mohamed Nazim and Tourism Minister Ahmed Adeeb and their shared antagonism of Home Minister Umar Naseer is also noted. Further, Islamic Minister Mohamed Shaheem and Home Minister Umar Naseer are named as having met gang members led by Muaz Hammer aka Gut Mua who is said to have initiated the meetings to discuss their concern “on the growth of secularsm” in the Maldives.

The public alliance of Defence Minister Mohamed Nazim and Tourism Minister Ahmed Adeeb and their shared antagonism of Home Minister Umar Naseer is also noted. Further, Islamic Minister Mohamed Shaheem and Home Minister Umar Naseer are named as having met gang members led by Muaz Hammer aka Gut Mua who is said to have initiated the meetings to discuss their concern “on the growth of secularsm” in the Maldives. The so-called religiously motivated “abductions” of the “Colourless” administrators took place after these meetings which were reported by the Government as “concerned youth” having met the ministers.

The so-called religiously motivated “abductions” of the “Colourless” administrators took place after these meetings which were reported by the Government as “concerned youth” having met the ministers.

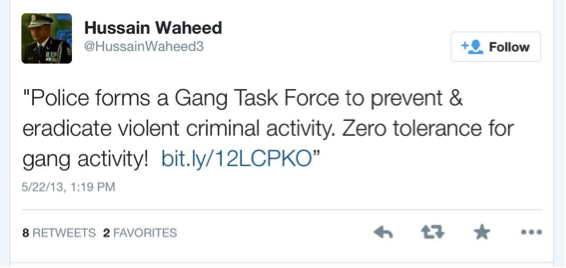

Last Sunday, following MDN’s announcement of the pending release of the PI’s findings, Commissioner of Police Hussain Waheed—who at the time was visiting Haa Dhaal Atoll with all the pomp of a politician—appeared to be reacting strongly against the #FindMoyameehaa movement led by friends and family of Rilwan.

Last Sunday, following MDN’s announcement of the pending release of the PI’s findings, Commissioner of Police Hussain Waheed—who at the time was visiting Haa Dhaal Atoll with all the pomp of a politician—appeared to be reacting strongly against the #FindMoyameehaa movement led by friends and family of Rilwan. Addressing the community, CP Hussain Waheed criticized the public demanding action from Police and is quoted as saying “MPS will not be swayed by people’s demands” and “MPS must not be infenced by any person or a group of persons”. Indirecty he referred to a public rally, #SuvaaluMarch (or Question March), led by family and friends of Rilwan demanding answers to questions related to the police investigation into the disappearance of Rilwan. Opposition leader, former President Mohamed Nasheed, and some senior politicians of Maldivian Democratic Party (MDP) had joined the rally to which family of Rilwan had personally written and invited all major parties to join.

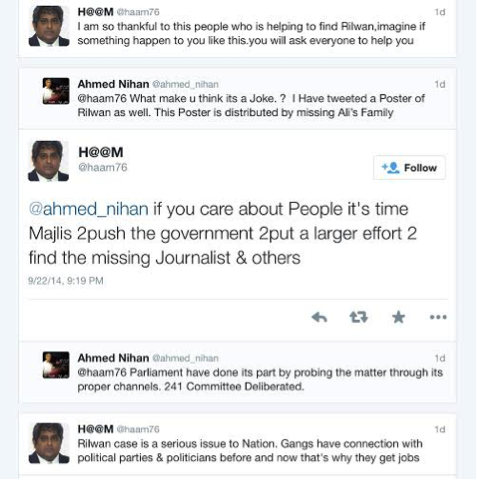

Addressing the community, CP Hussain Waheed criticized the public demanding action from Police and is quoted as saying “MPS will not be swayed by people’s demands” and “MPS must not be infenced by any person or a group of persons”. Indirecty he referred to a public rally, #SuvaaluMarch (or Question March), led by family and friends of Rilwan demanding answers to questions related to the police investigation into the disappearance of Rilwan. Opposition leader, former President Mohamed Nasheed, and some senior politicians of Maldivian Democratic Party (MDP) had joined the rally to which family of Rilwan had personally written and invited all major parties to join. Following the release of the PI report, the parliamentary majority leader, MP Ahmed Nihan of the ruling Progressive Party of Maldives (PPM), publicly ridiculed the #FindMoyameehaa effort with a tweet mocking the attempts to find him and belittling Rilwan’s disappearance. He then went on to shamelessly defend his action despite the wording on the poster he tweeted which contradict his claim it was an innocent act, and argued: “Parliament have done its part by probing the matter through its proper channels. 241 Committee deliberated.” Online supporters of PPM carried the same line, mocking and taunting those concerned about Rilwan’s disappearance.

Following the release of the PI report, the parliamentary majority leader, MP Ahmed Nihan of the ruling Progressive Party of Maldives (PPM), publicly ridiculed the #FindMoyameehaa effort with a tweet mocking the attempts to find him and belittling Rilwan’s disappearance. He then went on to shamelessly defend his action despite the wording on the poster he tweeted which contradict his claim it was an innocent act, and argued: “Parliament have done its part by probing the matter through its proper channels. 241 Committee deliberated.” Online supporters of PPM carried the same line, mocking and taunting those concerned about Rilwan’s disappearance.