First they came for Faafu

by Azra Naseem

1. Of Kings and Pawns

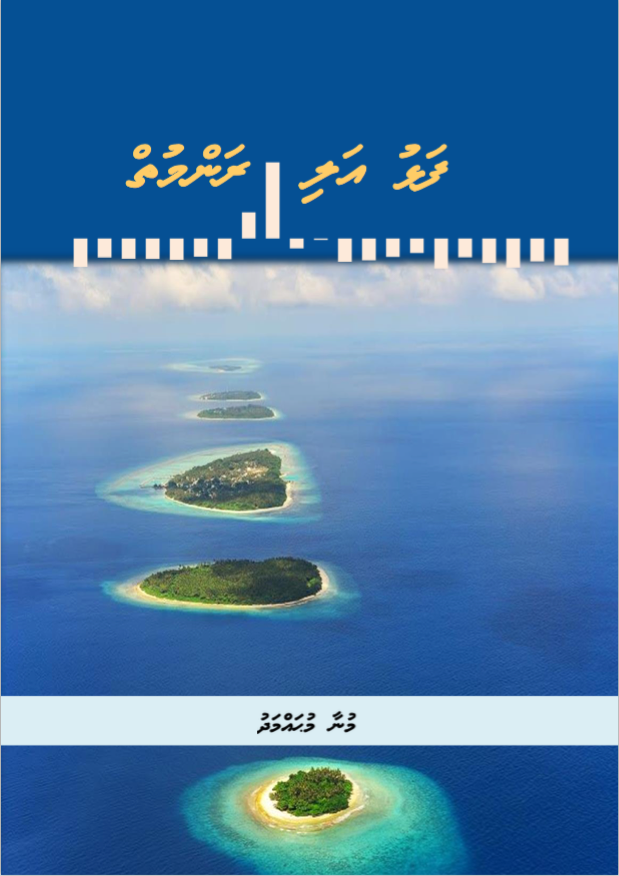

Just over a 100 kilometres south west of Male’, rising up from the deep blue lagoon, are 26 islands forming the atoll formally known as Faafu. This beautiful reef structure, one of twenty such natural island chains in the Maldives archipelago, is roughly 30 kilometres long and 25 kilometres wide. Five of the atoll’s islands are inhabited. Of the rest, four are under the jurisdiction of the Tourism Ministry, five leased on varuvaa[1], and five under the Atoll Council.

A sum total of just over four thousand people live on the islands of Feeali, Bileiydhoo, Magoodhoo, Dharan’boodhoo, and Nilandhoo the capital. Nilandhoo is large by Maldivian standards, measuring 56 hectares or half a square kilometre.

Faafu is historically significant. On Nilandhoo is the Maldives’ second oldest mosque, Aasaari Miskiyy, built over 800 years ago. As Norwegian explorer Thor Heyerdahl recounts in his book, The Maldive Mystery, he discovered the ruins of no less than seven Hindu temples and a Buddhist stupa on the island.

Life in Faafu goes a long way back; much further back than written Maldivian history is officially allowed to go.

Today Faafu is about to change beyond recognition.

Making Faafu Great

On 24 January President Yameen announced the atoll would soon see development ‘never before seen’ in the Maldives.

The president was speaking at a ceremony to inaugurate a ‘beautiful, modern’ mosque—gifted to the people of Magoodhoo by King Salman of Saudi Arabia. The new mosque, Masjid Al Taqwa, is not merely a place of worship, but a manifestation of the ‘special love and respect’ the desert monarch holds in his ‘noble heart’ for the islanders of Maldives. Maldivians would soon have the opportunity to welcome The King in person, said the President, God willing.

“Faafu Atoll is happy. And Faafu Atoll is lucky”, said the President. Because, Faafu is “an atoll that the Saudi government, or rather, leading figures in Saudi, have a special interest in”.

Fortunate Faafu, The Chosen Atoll.

Drawing out the suspense like the host of a cheap daytime TV gameshow, the President continued, “A huge massive project is planned for Faafu Atoll. All charts and drawings have been completed.”

In other words, the future of Faafu is a done deal. Drawn up and signed by the Saudi King and the Dhivehi President. Why should the people be consulted? Why should they have a say? They only live there.

The ‘Huge Massive Project’, Yameen said, could make Faafu the most prosperous atoll in the Maldives. “It will be open to the world, to people from all walks of life, travellers and such.”

It will be a township, he said. Presumably not Soweto in the Apartheid era.

“Only three or four such townships exist in the entire world”, he boasted. “It will set the standards for such projects”, and “will be copied” by future generations. The Faafu Township will be the giant on the shoulders of which future township visionaries will stand.

“That is what those elevated persons [the Royal Sauds] have in their noble hearts. We, too, have good hopes for this. We, too, are praying to Allah, that these things do happen to the Maldives, and that this will bring to Faafu Atoll the kind of development we have never seen before.”

That, and no more than that, is what the President cared to share. Pressed later by Mihaaru for details, his spokesperson said the government will “disclose information about its policies and initiatives as it sees fit”.

But, of course. The subjects must wait patiently for The King’s pleasure.

The questions people want answers to, meanwhile, frantically fly around public spaces on- and offline: How much of Faafu Atoll is the House of Saud taking for the so-called Huge Massive Township? Is it the entire atoll? If so, where are the people of Faafu to go? Will they be made to move en masse to Hulhumale’? If the Sauds are taking ‘only’ some islands, which ones would it be? What purpose the land? How much dredging and reclamation? With what consequences?

Land-grabs are, sadly, common across the poor world. Superrich global developers, with deep pockets and unlimited greed, criss-cross the earth with eyes keenly peeled for the perfect opportunity: natural beauty, corrupt leaders, and populations made weak by disasters both natural and man-made. Today’s Maldives combines those magic ingredients. It is breathtakingly beautiful, its people have been weakened by years of political unrest, societal strife, and continuous lack of prosperity. Most importantly, its leaders are immensely corrupt.

What more could the House of Saud—or the House of Trump, or whichever house sitting on whichever throne of dollars—ask for?

Sweeteners and sovereignty

Maldives has been courting Saudi benevolence for most of this decade. Dr Waheed, the ‘Immediate Past President’, before he finally handed the reigns over to Yameen, visited Saudi Arabia in July 2013. He met the then Crown Prince Salman, and successfully begged for money and patronage.

In March 2015, shortly after the Prince was crowned King, Yameen was granted an audience. The President returned with the promise of more money and a joint communiqué to facilitate investment opportunities in both countries. A US$20 million grant ‘to manage cash flow’ and a US$80 million loan for development projects were announced. Much more—an embassy right next to the President’s Office, additional loans, scholarships, Saudi-cabinet approved sponsorship of Maldives Islamic University—were to follow.

In July 2015, three months after that first visit of Yameen’s to Saudi Arabia, Article 251 of the Constitution forbidding sale of Maldivian territory to foreigners was up for amendment in the Parliament. To pass, it required a three-quarters majority.

Flush with Saudi endowments, the government made sure money was readily available for greasing palms—all the way from the parliament to the regional councils and island leaders.

Unconfirmed reports say part of Saudi money earmarked as sweeteners later went missing. Missing money—whether cash from Saudi as widely alleged, or stolen from MMPRC in the biggest embezzlement in Maldives’ known history—is at the heart of the epic fall-out between Yameen and his Vice President Ahmed Adeeb. Whether the cash handouts came from Saudi ‘generosity’ or from robbery of state coffers, that many MPs gladly received shares of the bounty is a known fact.

The amendment passed with ease. Only 14 out of 85 Members of the People’s Majlis voted against. The Ruling party PPM and its allies cited ‘mega development’ [always good]; the opposition MDP cited ‘being a centre-right party’ [free market always supreme]. These, people were told, were the reasons for pushing the Constitutional amendment through without so much as the customary eyebrow lifted in askance: what do you think?

11 of the seventy MPs who voted for the amendment were from MDP. Without their votes the proposal would have failed. In the days that followed, the party came into criticism from many members who, although in the minority, were vocal in their dissatisfaction. MDP secretariat shrugged off the criticism, justifying it by referencing its ‘centre-right position’. It was as if being centre-right, and being staunchly for neoliberalism, is a law written in stone MDP could not deviate from, whatever the cost.

MDP’s position on the proposed land amendment to the Constitution pic.twitter.com/O39EGVBkcN

— Hisaan (@hisaanhussain) July 22, 2015

Dangled before MDP MPs was also the promise of Mohamed Nasheed’s release from wrongful imprisonment. This—not cash in hand or party ideology—some MPs later claimed, was really what drove the MDP vote in favour.

Challenged on Twitter on Wednesday, MP Fayyaz Ismail (who voted against the amendment), explained that discussions within the party ahead of the vote largely agreed ‘the political situation’ should be the chief consideration for MPs casting the vote.

The ‘political situation’ MP Fayyaz referred to is widely understood to mean party leader Nasheed’s continued captivity and the chance to secure his release by voting the way Yameen, his jailer, wanted.

The potentially destructive power Yameen was granted through the constitutional amendment was an issue that could be confronted later, once Nasheed was released.

That this was an important part of the thinking behind MDP’s rationalisation of the majority Yes vote at the time is borne out by the party’s announcement on Wednesday that, (with Nasheed no longer at Yameen’s mercy,) the party will now do everything possible to repeal the amendment that would have been impossible without it in the first place.

Whither the immovable centre-right neoliberal position?

Until the vote cast on 22 July 2015, the constitution safeguarded Maldivian land by prohibiting both government and individuals from selling any of its territory to any foreign party. It was bad enough that the laws as they stood allowed leasing of islands for up to 99 years, in itself a moneymaking racket that has, over the years, created a rich/poor divide so great that less than a minute fraction own well over 99% of the country’s tourism wealth.

Laying claim to the Maldives for a century was not sufficient for the likes of the House of Saud. They need ownership. The government, therefore, engineered the second constitutional amendment with the Saudi Royal family in mind; just as it engineered the first constitutional amendment with Adeeb in mind. Now, all that an interested buyer has to do is invest US$1 billion (pocket change for the superrich), get some territory preferably with an island, reclaim enough lagoon so that the artificial land becomes 70 percent of the entire territory they’ve invested in, and voila, a piece of ‘paradise’ is theirs.

Opposition to the sale is intense, but lacks unity. Adhaalath Party is against, and it voted No to amending the Constitution. But it has only one member in parliament. MDP is against, but only because the government is not being transparent enough in doing the deal. Independent member Mahloof Ahmed–an influential voice, voted No. But he is in jail. Voices of JP and MDP MPs who went against the party position and voted No are subsumed by their parties that have been respectively unwilling and unable to oppose the sale effectively. Civil society campaigns, people-led movements, and vocal individuals, are mostly restricted to social media.

Generally, all dissatisfaction and angst–of party, society and individual alike–is kept in check by Yameen’s repressive policies that have banned democratic protests in the name of social harmony. Democracy is bad for development, he maintains.

The Maldives is on sale to the highest bidder. Islands, lagoons and reefs are going fast. At a time when the world has woken up to the calamities of man-made climate change, when sustainable development has come to the fore of the thinking person’s agenda, this most fragile of countries on earth lacks a unifying leader, party or movement that stands both in principle and practice, for people before profit, for sustainable development over short-term gain, and for development with consciousness over supplication to the so-called invisible hand of the market.

The future is bleak.

__________________________________________

First they came for Faafu II: Of Myths and Monsters

First they came for Faafu III: Muizzing Maldives

[1] A system of patronage dating back to the monarchy when rulers ‘gifted’ islands to favoured subjects. With the start of the tourism industry, the system turned into one of privilege and corruption, as will be explored in more detail later in this series.

Image: NASA