To be, or to conform, that is the question

by Azra Naseem

On International Human Rights Day 2011, a group of young Maldivians met in Lonuziyaaraiy Kolhu, Male’, to silently protest their lack of religious freedom. A similar protest had been held on the same day in 2010. Article 9 of the Maldivian constitution requires that all citizens be Muslims; and the State imposes an ever-increasing litany of punishments on those seen as falling short. Should the State fail in its ‘religious duty’ to punish such transgressors–as the aftermath of the small yet impactful protest revealed–Dhivehi Salafi Jihadists are ready, swords drawn, eager for their internal domestic Jihad: to maintain the ‘100 percent Muslim country’ status of the Maldives.

The 2011 silent protest marked the first physical altercation between Salafi activists and secular-minded Maldivians. On that December afternoon, Ismail Abdulraheem Adam, a Salafi Jihadist who would later be deported from Turkey while attempting to enter Syria, was among many such warriors who followed the protestors to Lonuziyaaraiy Kolhu. Abdulraheem hit Hilath Rasheed, a journalist and prominent blogger, on the head with a rock, cutting him.

It was the first in what would become many violent attacks on anyone in the Maldives insisting on advocating for rights not recognised by, or contrary to, Salafi beliefs, practices and teachings. Since then, two people linked to the protest have been murdered, another barely survived an attempted decapitation, and almost all the others who participated have been threatened, harassed, have no choice but to live in fear, or have had to flee the country. The attack on the protestors also set the tone for all future investigations into crimes committed by Salafi Jihadists and their non-/less-violent brothers: nobody will be punished; not even in the face of overwhelming evidence to convict.

Police knew who attacked who and why on 10 December 2011. They arrested no one.

Five months later, on 10 May 2012, Abdulraheem, acting with two fellow Jihadists, attacked Hilath again. “Repent, repent! We don’t know, the public doesn’t know, you have repented!”, they shouted, hitting him around the head, surrounding him with motorcycles.

Only weeks later, on the evening of 4 June 2012, they returned to slit his throat. Three Dhivehi Salafi Jihadists, waited for him to return home from work late at night, cut his throat with a Stanley knife, and left him to die outside his home.

Hilath lived to tell the tale; but no one listened, really.

Allowed to get away with murder, the Jihadists widened their campaign to rid Maldives of any citizens that dared contradict their manhaj, or disagreed with their teachings. They found their next prey within a few short months.

MP Afrasheem Ali was a politician with a doctorate in Usul al-Fiqh from the Islamic University of Malaysia noted as a rising star in conservative politics. For several years after he returned from Malaysia in 2007, Maldivian Dheenee I’lmverin–dominated by Adhaalath Party and other Salafi influencers such as Jamiyyath Salaf–ostracised Dr Afrasheem for “contradicting the manual of the Salaf al Salahin”, for suggesting music may be as pleasing to the ear as the sound of Qur’an, for not using the appropriate language to address the Prophet Muhammad, and among other things, for saying beards are not necessary for men. Basically, for not aligning his thinking with Salafi thinking. Afrasheem was banned from expressing his opinions and forbidden from leading prayers unless he repented. Endorsed by Adhaalath and other Salafi leaders, followers harassed Afrasheem online and on the streets, sometimes violently, once in a mosque in the presence of his young son. His religious opinions—which included endorsement of practices dominant Salafi clerics rejected as bid’a—were deemed unfit for the Modern Maldivian Muslim. A definition that must be approved by Salafi leaders to be accepted as true.

In the early hours of 2 October 2012, Afrasheem returned to his apartment on the south-eastern waterfront of Male’ after appearing in a late-night show, Islamee Dhiri-ulhun, on state television. He parked his car, entered his apartment building, and was walking up the stairs to his flat when three Jihadists attacked him on the stairwell. He had finally given into the immense pressure on him to conform or else; and agreed to appear on public television to repent. The station, channel and programme on which he should do so was decided by those demanding this public spectacle of him. Adhaalath Party held a special screening in their headquarters to gauge his performance. The killers knew exactly where he would be and when that evening. Afrasheem tried to explain his aqida on TV that night; and he apologised–for expressing his own opinion. However well-informed, considered or well-intentioned it was, it was not valid for it contradicted The Most Learned Men of Salaf Jamiyya, Adhaalath and other such groupings.

Despite the apology, Afrasheem was unable to save himself. They still cut his throat.

When the news of his murder reached the leader of Salaf Jamiyya, he responded: “It was an atrocity in Islam to kill Afrasheem after he had admitted to his sins and after he repented last night”. Without repentance, he had been fair game.

Afrasheem has now been dead almost 10 years. It is now known Dhivehi Salafi Jihadists, operating domestically as one among several Al-Qaeda cells, were behind the planning and the execution of Afrasheem. They have not been prosecuted.

The dust may seem to have settled on the murder of Afrasheem’s death with no consequence for those who laid the plans and paid for it. Society, on the other hand, paid a heavy price. No religious scholarly longer dares publicly challenge the Salafi doctrine in the Maldives.

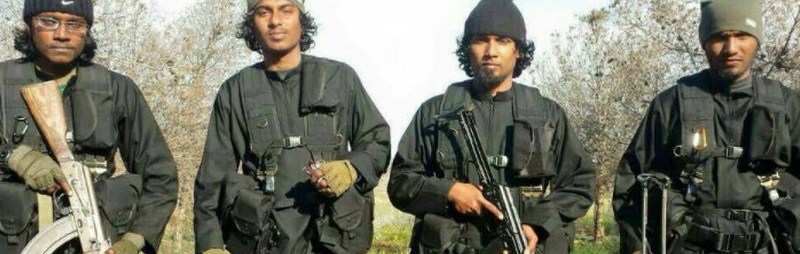

In July 2014 Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi of the ISIS declared an Islamic Caliphate from Iraq, further emboldening Maldivian Salafi Jihadists, both as foreign fighters and as local warriors on a holy mission to cleanse Maldives of the secular and the shirk. Less than a month later, in the early hours of the morning of 8 August 2014, Jihadists kidnapped Ahmed Rilwan, a journalist and blogger. At the time he was covering the activities of Maldivan Jihadists flocking to the conflicts in Syria and Iraq as a journalist for Maldives Independent. One Dhivehi Jihadist in Syria accused Rilwan of not being a proper Muslim and issued a warning that his days were numbered.

Just as the earlier Jihadists waited outside the homes of Hilath and Afrasheem with their sharpened blades hidden in the darkness of the night, they waited for Rilwan outside his home in the early hours of the morning. Instead of decapitation on the spot—the apparent goal behind both previous attacks—they kidnapped Rilwan, bundled him into the boot of a red car, forced him onto a boat, took him out into the open ocean, and made him recite the Shahadha. Then they decapitated him.

Rilwan’s family only learned of his fate in 2019, years after the Jihadists abducted him. They are still campaigning for justice. In vain.

On this day four years ago, Salafi Jihadists picked their next target: Yameen Rasheed, 29, a blogger and writer who not only disagreed with the Salafi vision for the Maldives but also often satirised various aspects of it online. Yameen and Rilwan shared more than an ideological kinship; they were also bound by strong ties of friendship. After Rilwan’s forced disappearance in 2014, Yameen dedicated much of his energy towards campaigning with Rilwan’s family for justice. In vain.

On 23 April 2017, Yameen returned home from work in the early hours of the morning. The Jihadists were waiting for him in the darkness of the stairwell inside Yameen’s apartment building. They stabbed him 34 times in a frenzied attack. His cries for mercy fell on deaf ears. The young writer died in hospital later that morning. Yameen’s family now dedicates much of their energy to campaigning with Rilwan’s family for justice. In vain.

Salafi Jihadists are allowed to kill non-conforming Maldivian citizens with impunity.

A Maldivian citizen that openly criticises Salafi beliefs, teachings and practices—does not matter whether you are a pious Muslim; a scholar of Islam; a ‘moderate Muslim’; a relaxed one; a lapsed one; an apostate or an atheist—can be, has been, and will be killed. And the Jihadists who kill them will remain unpunished. The reason is simple: the government and most of contemporary Maldivian society accepts death—or at the very least expulsion from society—as a suitable form of punishment for citizens identified as insufficiently Muslim, anti-Islam, or Enemies of Islam. ‘LaaDheenee’ people, marked as such by Salafi influencers according to their own criteria, are made into figures of public hatred to such an extent that Jihadists feel they must kill them to rid their society of Kuffars, and the public feels convinced the killing was for the ‘greater good’ of the ‘100 percent Muslim’ country.

That is why the courts of law in the democratic republic of Maldives are failing to deliver justice in these killings. According to the religious ideology that dominates the entire government and state apparatus, and most of society, true justice has already been done. By killing these men.